All official European Union website addresses are in the europa.eu domain.

See all EU institutions and bodiesForest ecosystem services: what are they and why are they important?

When we think about the positive role that forests provide to society we tend to immediately think about them as a source of timber for the construction of wooden buildings, furniture, fencing and everyday items that we use around our homes.

However, when we pause a little longer to ponder the goods and services that forests deliver, we’ll soon come up with a longer list of benefits. To mention just a few: our forests define our familiar landscapes and create a sense of place, provide a haven for wildlife and biodiversity, provide healthy outdoor spaces for people, protect and regulate our water supplies, filter the air that we breath and supplement our diet with wild foods. The diverse benefits which people derive from nature are referred to as Ecosystem Services. The Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services . Here we will focus on the specific contributions provided by forested ecosystems.

Fig. 1. Recreation and education are important Ecosystem Services offered by forests

So, in more detail, what are forest ecosystem services?

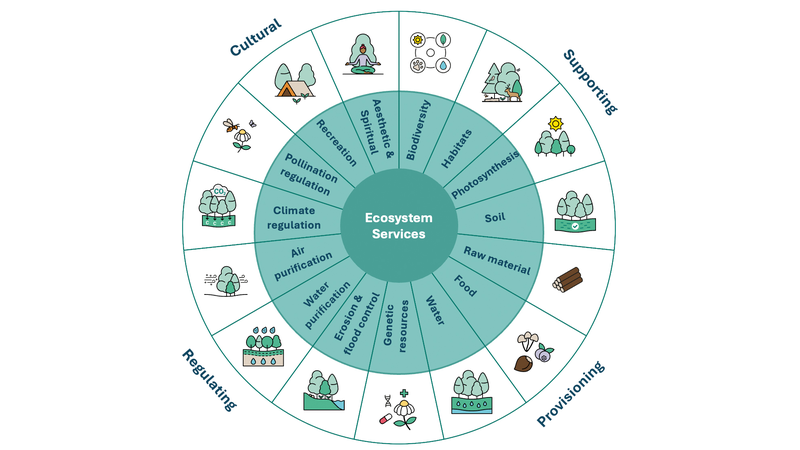

Forests are quite literally rooted in nature, with biodiversity providing the starting point for all ecosystem services. Ecosystem Services themselves were classified according to the Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) into four categories: provisioning, supporting, regulating and cultural services (these have been more recently aggregated by CICES into 3 broader categories). In more detail, examples of Ecosystem Services according to the MEA classification can include:

- Provisioning services: Timber, fuelwood, berries, mushrooms, game, and genetic resources.

- Regulating services: Carbon sequestration, water regulation, flood control, air and water purification, soil retention, and pollination.

- Cultural services: Recreation, aesthetic value, spirituality, and education.

- Supporting services: Biodiversity, photosynthesis, nutrient cycling, and habitat provision.

Fig 2. Range of ecosystem services provided by nature to humans.

Source: Adapted from European Forest Institute 2014

It’s a numbers game - Forest Ecosystem Service (FES) accounting

Just as in our own financial management systems, nature’s flows of goods and services can be accorded a value which can be calculated. Ecosystem accounting provides a structured approach to better understand and manage these flows. It integrates ecological data with economic statistics to measure the contributions of ecosystems to the economy and to human well-being, while tracking the overall condition of ecosystems and their capacity to deliver services over time. The integration of ecosystem services with economic accounting reveals the large and often undervalued contribution of forests to European society.

How are forest ecosystem services accounted for?

Ecosystem services are accounted for through the SEEA EA (System of Environmental-Economic Accounting – Ecosystem Accounting) which uses a structured approach to track ecosystem extent, condition and service flows in both physical and monetary units. The EU supports SEEA EA through the Integrated Natural Capital Accounting (INCA) Project, which is used to report through use of supply and use tables.

At an individual project level, the Total Economic Value is an important common decision support tool for Ecosystem Services. Total Economic Value in Ecosystem Services refers to the accumulated value of all benefits that humans derive from nature, encompassing both use (direct, indirect, option) and non-use (existence, bequest) values. The Total Economic Value is then utilised for cost-benefit analysis to compare the monetary value of ecosystem benefits (which often lack market values) against the costs of projects or policies. Similarly it can be used to also compare non-environmental project benefits versus environmental costs. By quantifying these values, decision-makers can evaluate trade-offs to ensure that the full, comprehensive economic implications, including environmental impacts, are considered when making policy decisions.

The value of Ecosystem Services to the EU in general has risen steadily over the years. A recent INCA report revealed an estimate of the economic value, provided by a wide set of Ecosystem Services in the EU, amounted to EUR 234 billion in 2019, which is comparable to the gross added value of agriculture and forestry combined. By comparison, INCA suggested that the value of the seven ecosystem services totalled EUR 172 billion in the EU in 2012. Forests deliver 47.5% of the total supply of the seven measured Ecosystem Services whilst croplands contribute 36%.

Why is the valuation of forest ecosystem services important ?

The increasing understanding of the value of Forest Ecosystem Services (FES) has significant implications for Forest Policy. Ecosystem accounting influences land use decisions on the ground, restoration priorities and broader EU policies, through helping to target funding initiatives. Forest Ecosystem Service flows can provide multiple benefits across the full range of categories. This is crucial for policy by helping to quantify trade-offs and guide restoration or land-use change decision making. By integrating forests into ecosystem accounting procedures, the EU can support better decision-making for forest management, land-use planning and climate policy, thus ensuring the sustainability and resilience of critical ecosystems.

Keeping the FES balance sheet healthy

Securing the supply of FES in the medium to long term is challenging task. It requires a systems-based approach which recognises the interconnections between forest ecosystems, their management, resilience and adaptive capacity. To address this issue, it is firstly important to understand the potential threats to FES provision. These include climate change, changes in land use and the unsustainable exploitation of natural resources. Maintaining healthy ecosystems and their structure and functions is vital to address these impacts. Positive management interventions, such as adaptation to climate change (which poses the greatest challenge for maintaining diverse FES), ecological restoration or habitat enhancement, offer potential to increase the range of benefits, whilst mitigating against threats.

The adoption of sustainable forest management practices which integrate ecological, economic and social benefits is critical to maintain forest structure and functions in the longer term. Management practices should aim to increase the overall resilience of forests. Resilience refers to the forests’ ability to withstand shocks such as drought, pests and diseases whilst maintaining longer-term viability of forest ecosystems. In practice, diverse and structurally complex forests are most likely to be resilient.

Securing the supply of forest ecosystem services

It’s clear that there is a need to better incentivise closer-to-nature forestry and other management systems aiming to promote resilient multifunctional forests through developing and nurturing innovative business models to preserve and increase flows of Forest Ecosystem Services. (see: Guidelines on Closer-to-Nature Forest Management - European Commission)

Fig. 3. Pollination is an important Forest Ecosystem Service

The management of forest ecosystems is likely to involve a range of different models or elements which operate together in combination. One important mechanism for achieving this is through Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) Schemes. Payments for Ecosystem Service (PES) programs are designed to provide incentives for landowners to manage their land in a way which delivers environmental benefits that are normally not renumerated, such as water supply regulation, carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation and habitat connectivity. To enable this, forest managers can establish "ecosystem service contracts" which they are paid out for the wider environmental benefits that forests provide. Through preserving natural habitats, businesses can maintain or enhance the services which the forests and natural ecosystems provide, making close-to-nature management an integral part of the strategy.

Public and private payments for forest ecosystem services represent an alternative option to secure financial sources for multifunctional and protective forest management and sustainable maintenance of ecosystem services. PES schemes often involve a set of rules, procedures and requirements to incentivise and reward economic operators for carrying out additional activities that can increase the provision of one or more ecosystem services. They can be an effective tool to provide financial incentives to forest owners and managers to provide enhanced FES through forest protection, restoration and sustainable forest management (such as increasing the diversity of tree species, structural diversity and un-even aged silviculture).

Developing markets for ecosystem services beyond carbon sequestration, including water quality, flood regulation, and biodiversity, will further expand the scope of PES. Governments can partner with private companies to design and implement PES programs that benefit both the environment and the economy. Encouraging businesses to incorporate PES into their corporate sustainability strategies and supply chains can encourage large-scale investments in forest conservation.

The EU Forest Strategy’s aims to further encourage the establishment of PES schemes through Commission guidance, published in 2023, revised State Aid guidelines and the Carbon Removal and Carbon Farming regulation. Similarly, the nature credit initiative announced by the European Commission aims to incentivise private investments into nature-positive actions that protect and preserve ecosystems, including forests. This will offer new income opportunities for foresters while helping them to restore ecosystems and bolster the resilience of their businesses.

Whilst restoration efforts might be funded effectively through individual landowners, there is also potential for the creation of innovative landscape scale partnerships involving commercial landowners, local communities, government agencies and NGOs working collaboratively to maximise the spread of benefits and minimise the administrative burden such as the Cairngorms Connect Project in Scotland.

Fig. 4. The Cairngorms Connect Project is a good example of diverse partners working together on a landscape scale to improve Ecosystem Service delivery.

Blended finance, involving a mix of public and private funding, can also help to lever philanthropic donations and external funding and to unlock further investment. Alternative financing such as attracting private investment through impact investing and green bonds can also provide capital for close to nature forestry. Such mechanisms can provide financial returns to investors while contributing to biodiversity conservation and climate resilience. The process can be further assisted by governments offering tax breaks or subsidies for businesses and landowners who engage in sustainable forest management and conservation.

Whilst the upscaling of finance in restoration is imperative if global restoration targets are to be met, it is important to acknowledge that private finance objectives might not always align with wider societal justice and sustainability principles. Indeed, incentives can sometimes benefit investors to the detriment of local communities, perpetuating inequalities or divisive patterns of historical ownership. Within Scotland, for example, there has been a longstanding debate around the role of so-called “Green Lairds” who buy large tracts of land for philanthropic or investment purposes. Whilst, undoubtedly, green investors can bring about positive benefits for ecological restoration and delivery of FES, reported negative impacts have also included inflated land markets, lack of local accountability and potential restrictions upon public access.

Support for community-based Initiatives and cross sector partnerships

Funding and policy support needs to ensure that social justice principles are fully enshrined within PES policies. This will ensure local communities are not excluded from market access or from the opportunities accorded to external investors and speculators. Empowering local communities by recognising land rights and traditional knowledge of sustainable forest management should therefore play a fundamental role in the upscaling of PES. Community based management approaches can potentially bring substantial benefits including innovative thinking, unlocking financial and in-kind resources, developing local capacity, fostering a sense of common stewardship and the creation of diversified and responsive governance structures.

Significantly, ensuring that landowners and local communities possess the necessary skills and knowledge to engage in PES through effective capacity building is essential. This might require training in diverse skills such as sustainable forest management, accessing finance or legal frameworks. To facilitate this process, the EU have produced a good practice guide on payment schemes for Forest Ecosystem Services which can be found here.

Integrating knowledge and action on the ground through provision of best practice case studies and technical support will help to upscale PES programs across different landscapes and ecosystems. To this end, a number of EU Horizon funded projects have investigated how forest restoration activities can be upscaled across Europe in partnership with local communities, landowners and other partners to deliver increased Ecosystem Services benefits. The INNOFOREST Project, the SINCERE Project and the INTERCEDE Project are examples of EU Funded Horizon Projects which have been addressing the issue of upscaling delivery of Forest Ecosystem Services (see Case Studies 1 and 2 below).

Case Study 1. INNOFOREST - Payments for ecosystem services

The EU Horizon-funded InnoForESt Project aimed to transform the European forest sector by fostering innovation in the sustainable supply and financing of forest ecosystem services. It supported innovation through multi-stakeholder networks, pioneering policy tools and new business models. Six real-world pilots demonstrated diverse, region-specific approaches:

- Austria: Boosting value in regional wood processing

- Finland: Biodiversity conservation via novel payment schemes

- Germany: “Forest Shares” for climate protection

- Italy: Active forest management for multiple functions

- Slovakia/Czech Republic: Collective action for climate regulation

- Sweden: Promoting fascination with forests

Core common elements included; (i) Multi-actor networks, (ii) Innovation platforms, (iii) Facilitated processes for business and policy and, (iv) Policy-relevant data and recommendations. InnoForESt fostered collaboration, learning and the exchange of best practices. Results have been used to explore EU-wide scalability, contributing to a roadmap for sustainable forest ecosystem services and improved policy coordination.

For further details see: https://innoforest.eu/

Case Study 1. INNOFOREST Project – Payments for Ecosystem Services

Diversification of production systems and through non-timber forest products (NTFPs)

Other potential mechanisms for increasing the flow of ecosystem services include the diversification of land use, the types of production and through increasing the range of products harvested from the forest, for example through agroforestry and silvo-pastoralism. In addition to timber production, many other diverse non timber forest products (NTFPs) can be harvested from forest lands, including fruit, nuts, mushrooms, wild game, medicinal plants and resins.

Within specified limits, these products can be harvested sustainably, thereby diversifying the range of ecosystem goods and services available from the forest. However, the gathering of NTFPs on a commercial scale must ensure sustainable practices to avoid overharvesting or damaging the resource. Effective regulation and monitoring of foraging activities can address such issues, often using new technologies such as online apps (see Case Study 2).

Case Study 2. The SINCERE Project. Mushroom gathering in Borgotaro forests of the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines

The Borgotaro forests in the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines, Italy, feature sustainably managed sweet chestnut and beech stands, providing wood products and Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFP) like mushrooms. Mushroom gathering is popular and has traditionally been regulated by permits. To streamline this process, a new mobile app has been developed, allowing users to purchase permits online and navigate designated picking areas, thereby enhancing safety and user experience. The app also helps forest managers to control mushroom picking intensity, subsequently reducing conflicts and overharvesting. Generated funds are being used to support diverse Forest Ecosystem Services schemes and community projects. This innovation could be replicated in other Italian forests and adapted for regulating activities like mountain biking and hiking; however, opportunities in other European countries may be limited due to legal rights regarding outdoor access and foraging.

Case Study 2. The SINCERE Project. Mushroom gathering in Borgotaro forests of the Tuscan-Emiln Apennines [24]

Ecotourism and nature-based tourism enterprises

Ecotourism (often used interchangeably with nature-based tourism) initiatives can provide an incentive for sustainable forest management and biodiversity protection through the promotion of forests (particularly in areas of high biodiversity or landscape value) as locations for experiencing nature.

Fig. 5. Mushroom Gathering is a traditional activity which can be better regulated to enhance Ecosystem Service delivery

Fig. 6. Ecologically intact regions such as Romania’s Carpathian Mountains offer potential to diversify Ecosystem Service delivery through ecotourism initiatives

Nature-based tourism can create a sustainable economic model which can also facilitate the long-term stewardship of territories which host ecotourism activities (in contrast to exploitation for short term profits, such as through unsustainable logging). Businesses which generate income from ecotourism therefore have a strong incentive to protect the environment which supports their economic activities. Meanwhile, there can also be knock on benefits for the wider local economy, including for accommodation, transportation and gastronomy providers. Such local benefits can provide a wider economic incentive for establishing and maintaining protected areas through public funding (when such activities are managed sustainably). In recent years there has been growing interest in some of Europe’s more biodiverse and ecologically intact regions such as Romania’s Carpathian Mountains as locations for ecotourism initiatives (see Case Study 3). The LIFE Carpathia Project is a good example of a multi-stakeholder initiative which has received funding from diverse sources including EU LIFE funding.

Case Study 3. The LIFE Capathia Project – Ecotourism, biodiversity and local food production

The Carpathian Mountains host some of Europe’s largest contiguous forests, rich in biodiversity and home to the continent’s largest populations of large carnivores. Since 2005, forest restitution in Romania has led to significant deforestation. In response, Foundation Conservation Carpathia was founded in 2009 to combat illegal logging by acquiring land and leasing hunting rights through public and private funding.

The LIFE Carpathia Project promotes eco-tourism as a sustainable income source for local communities, focusing on the Făgăraș Mountains. It supports infrastructure, training, and promotion for nature-based tourism, including wildlife hides, guided tours, and multi-day itineraries, thereby diversifying the range and type of Ecosystem Services.

The project has launched 10 conservation-related enterprises to improve conservation, generate jobs and to support protected area management. Notably, Cobor Farm combines biodiversity farming, heritage architecture and eco-tourism. Additionally, “The Fruits of the Mountains” food hub connects sustainable local products with broader markets, supporting responsible farming and young entrepreneurs.

Case Study 3. The LIFE Capathia Project [26]

In summary – Upscaling the provision of FES

To secure forest ecosystem services in the longer term, we must integrate sustainable forest management with climate resilience and adaptation, backed by science, local participation, and supportive governance. Ultimately, forests which are ecologically healthy, socially supported and adaptively managed will be best positioned in the future to continue delivering critical ecosystem services under challenging conditions.

The future upscaling of payments for forest ecosystem services (PES) can make a significant contribution for supporting landowners in conserving biodiversity whilst adopting closer to nature forestry principles which addresses the multiple demands of society and the longer-term impacts of climate change. To achieve this effectively, a multi-faceted approach is required involving the creation of supportive policies, effective financing and innovative partnerships between stakeholders.

- a bEuropean Environment Agency, “CICES Towards a common classification of ecosystem services ,” https://cices.eu/#:~:text=In%20CICES%20ecosystem%20services%20are,people%20subsequently%20derive%20from%20them.

- World Resources Institute, “Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. ,” Washington D.C., 2005.↵

- B. Jellesmark Thorsen, R. Mavsar, L. Tyrväinen, and I. Prokofieva, “The Provision of Forest Ecosystem Services. Volume I: Quantifying and valuing non-marketed ecosystem services. What Can Science Tell Us,” Joensuu, Finland, Oct. 2014.↵

- ↵United Nations, “Introduction to SEEA Ecosystem Accounting,” https://seea.un.org/introduction-to-ecosystem-accounting.

- ↵European Commission, “About INCA Ecosystem accounting framework,” https://ecosystem-accounts.jrc.ec.europa.eu/about-inca.

- U. Pascual, M. Verma, B. Martín-López, R. Muradian, L. Brander, and E. Gómez-Baggethun, “The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations,” in The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations, 1 ed., P. Kumar, Ed., London: Taylor & Francis, 2012, ch. Chapter 5. doi: 10.4324/9781849775489.↵

- ↵E. Plottu and B. Plottu, “The concept of Total Economic Value of environment: A reconsideration within a hierarchical rationality,” Ecological Economics, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 52–61, Feb. 2007, doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.09.027.

- a bEuropean Union, “Accounting for ecosystems and their services in the European Union (INCA),” Luxembourg, Apr. 2021. Accessed: Jul. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/7870049/12943935/KS-FT-20-002-EN-N.pdf

- ↵European Union, “Ensuring that Polluters Pay: Payments for Ecosystem Services,” https://environment.ec.europa.eu/economy-and-finance/ensuring-polluters-pay/payments-ecosystem-services_en.

- ↵I. Grover, J. O’Reilly-Wapstra, S. Suitor, and D. Hatton MacDonald, “Not seeing the accounts for the forest: A systematic literature review of ecosystem accounting for forest resource management purposes,” Ecological Economics, vol. 212, p. 107922, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107922.

- ↵FAO, “Sustainable Forest Management,” https://www.fao.org/forestry/sfm/en.

- European Commission, “Guidelines on Closer-to-Nature Forest Management,” Brussels, Jul. 2023.↵

- European Commission, “Guidance on the Development of Public and Private Payment Schemes for Forest Ecosystem Services,” Brussels, SWD(2023) 285 final, 2023.a b c d e

- I. Viszlai, J. Barredo Cano, and J. San-Miguel-Ayanz, “Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services - SWOT Analysis and Possibilities for Implementation,” Luxembourg, Oct. 2016.↵

- ↵S. Underwood et al., “Case studies in large-scale nature restoration and rewilding: Learning from existing projects - NatureScot Research Report No. 1271,” 2021. Accessed: Jul. 21, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.scot/sites/default/files/2022-03/LSNR%20and%20Rewilding%20Case%20Studies%20-Key%20Findings-%20%20accessible%20-%2031-3-22%20%28A3694998%29.pdf

- ↵S. O. S. E. zu Ermgassen and S. Löfqvist, “Financing ecosystem restoration,” Current Biology, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. R412–R417, May 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.02.031.

- J. J. G. Robbie, “Carbon Markets, Public Interest and Landownership in Scotland - A Discussion Paper,” Inverness, 2022.a b

- L. Paltriguera and A. Markowska, “ Payment schemes for forest ecosystem services – Support for implementing the new EU Forest Strategy for 2030,” Luxembourg, 2025.↵

- a bInnoforest, “InnoForest,” https://innoforest.eu/.

- ↵SincereForests.eu, “SINCERE - Innovating for Forest Ecosystem Services,” https://sincereforests.eu/.

- ↵intercede-project.eu, “INTERCEDE Project,” https://intercede-project.eu/.

- ↵M. K. Roy, M. P. Fort, R. Kanter, and F. Montagnini, “Agroforestry: a key land use system for sustainable food production and public health,” Trees, Forests and People, vol. 20, p. 100848, Jun. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.tfp.2025.100848.

- B. Wolfslehner, I. Prokofieva, and R. (editors). Mavsar, “Non-wood forest products in Europe: Seeing the forest around the trees,” Joensuu, 2019.↵

- ↵A. Mortali and E. Vidale, “The Mushrooms of Borgotaro IGP,” 2022. Accessed: Jul. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://sincereforests.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/SINCERE-findings_08_italy-borgotaro.pdf

- ↵European Forest Institute Biogateway, “Nature-based tourism: a growing sector of world bioeconomy,” https://biogateway.efi.int/nature-based-tourism-a-growing-sector-of-world-bioeconomy/.

- ↵Carpathia, “LIFE Carpathia - About the Project,” https://www.carpathia.org/life-carpathia-en/.